Libera me: An Invitation, a Story, a Gift, and a Question

ABOUT THIS INTRODUCTION

This presentation was part of a program with the Montclair State University Chorale, conducted by Heather J. Buchanan. In between the movements of Verdi’s Requiem, I presented some images of the manuscripts from the movement, Libera me, and discussed the relationship between music-making and the historical imagination. In what ways can music-making strike a balance between doing and reflection? If we could articulate this relationship what would it teach us about this work, where it came from, and our relationship to it? I characterized my own approach to the Libera me as that of a reflective witness. Verdi’s music is a testament to his private questions but it survives in ways that he never could have imagined.

PERFORMANCE SCRIPT

“Behind-the-Scenes” began as a conversation about artistic process – about the relationships between music-making & the historical imagination. If you’ll indulge me for a moment, I’d like to explain how this conversation occurred because it will clarify the ways that Verdi’s music forms the starting point for a Story, a Gift and a Question.

It began with a question: in what ways can music-making strike a balance between doing and reflection? If we could articulate this relationship what would it teach us about this work, where it came from, and our relationship to it? This required some lab time. I cast myself into the role of a silent witness in rehearsal. I watched the choir navigate Verdi’s work and tried to reflect on that act.

Let me offer you an example. If you go to the last part of the Requiem text in your program, you will find the Libera me (“Deliver me”). Verdi’s setting of these words provides a visceral lesson about the tension between the individual and the collective. The parts imitate each other but at different times, so that each line is offset from the other. We call it a fugue – by composing this way Verdi draws on a venerable musical form. The parts are at once the same, and fiercely independent. They contract and expand against each other. As a choir, we might learn our parts mechanically at first, like the teeth in a complex gear system, locking powerfully into their forward motion. But to make sense of a fugue, from the inside out, you must not only be an agent of your own motion but also precise about the space you inhabit. In the most urgent way, a fugue demands your awareness of both the moment and the future.

Thinking historically can be like this. It can shed light on the mechanisms of the past to suggest ways to move forward. It requires that you live comfortably with paradox. It demands that you act from the seat of your own uniqueness, to survive the infinite variety of other stories. In sum, it is a way of understanding of your place in the world.

In the Metropolitan Museum in New York, there is a small case with the remnant of a haunting face, a sculptural fragment in yellow jasper – the face of a noblewoman who lived over a thousand years before Christ. We know almost nothing about her. We do not know her name, or her place in her community. We are left only with imprint of her elegant mouth and the strong line of her jaw. How do we make sense of her? What could she mean to us, even in this fragmentary form? We might hold her in our gaze for a moment until the fragment carves a place in our mind’s eye, until we can turn away and see it ghosted onto our world. We could mourn her loss, in the sense of paradises we have lost.

But what if we asked a different sort of question? What if we imagined her into being from where we stand now – in an imaginative reversal of history. Perhaps she would be less if she was whole … perhaps she doesn’t need completion but rather an act of creation. We could use her enigmatic expression as a pivot to re-imagine her into the world. How would the length of her body move through space? Could we reconstruct her not out of a mechanical curiosity, but instead from the desire for solace?

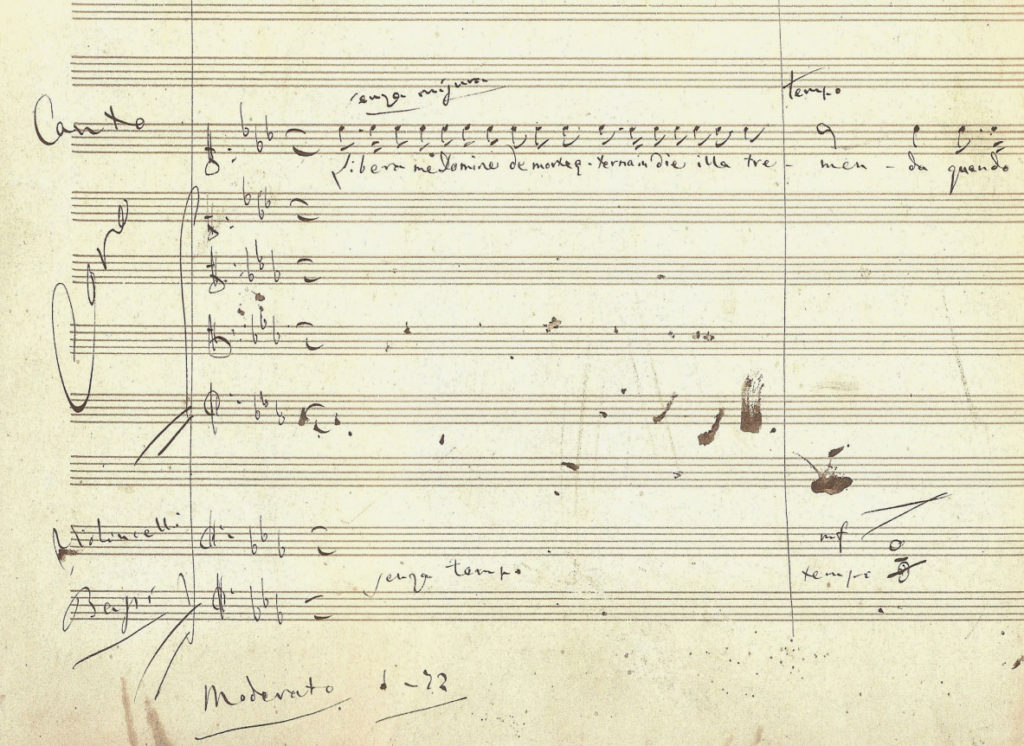

In the early part of the 1870s, Verdi re-imagined a body of sorts. He took his own setting of the Libera me text, which he had completed five years earlier and he began to imagine his own complete work. What you see here is this first setting, dated 1869. As he studied this manuscript, Verdi began to imagine the possibilities for a monumental form, a body that would be drawn from its likeness.

We’re going to listen to that finished “body” tonight as it unfolds in time, but perhaps we could also think about Verdi’s work from the end to the beginning … in other words, trace the way it was written, as it blossomed from the end. The presence of this earlier manuscript makes this sort of re-imagining possible. It can transform our understanding of this work and its central questions. Perhaps even more importantly, for the people on this stage, it highlights the act of music-making, and for you, the act of listening. We all can, nay we must, build our own Requiem from the ground up. Verdi begins with the orchestra and the choir, a musical shadow that will return in the last movement with the aid of the soprano.

PERFORMANCE: REQUIEM AND KYRIE

From its earliest conception, the Requiem has been a powerful mirror for anxieties about belonging. The mirror was private and public – private, in that Verdi saw its potential to glorify the things he held most dear – and public, in that the work generated debate about the essence of Italian music.

After all, nations imagine themselves into being too. They are also the product of perception. In the nineteenth-century many larger communities in Europe were engaged in this kind of imagining. They were doing what communities often do when trying to build a collective identity. They fashioned their stories by explaining – often in humorous or ruthless terms – how they were superior to their neighbors. For the Italians, it was the Germans to the north that caused the most anxiety. When Verdi conducted his Requiem for the first time in Milan in 1874, Italian ambivalence over the Franco-Prussian War was still fresh and the Italians themselves had just ended a long process of unification. Verdi claimed that his Requiem memorialized the famous Italian poet Alessandro Manzoni – in sum, a tribute by one great embodiment of Italian culture to another. But like so many other works by major composers offered in the public arena, the Requiem became a convenient target for thinly-veiled politics.

In one of the more famous examples of this kind of cultural anxiety, the noted German conductor, Hans von Bülow wrote that Verdi’s new work was nothing more than an Oper in Kirchengewande (opera in ecclesiastical dress). Whether or not Verdi actually committed a transgression by allowing the drama of the stage to inform the language of the liturgy wasn’t really the point; better to think of it as yet another way that Verdi’s work became a kind of cultural dartboard. In addition to providing juicy entertainment for the Italian press, Bülow was re-enacting an old aesthetic argument from home, which usually painted a picture of Beethoven as the embodiment of truth and Verdi’s predecessor, Rossini, as the incarnation of a shallow beauty.

The Requiem was also a private mirror, one perhaps less easy to identify, but more potent for our twenty-first century perspective. In fact, Verdi himself was ambivalent about the whole business of religion. He was a self-proclaimed agnostic. For the people on this stage, this fact has been a source of animated conversation over the last weeks. It goes something like this: “Clearly it would be preposterous to suggest one has to be a devout Catholic to write good Catholic music.” And then … “But it can’t be true that this music is sacred just because I’m convinced it is. Am I dreaming? Look at my part. This music does have the exquisite force of conviction.”

Now for my own confession: I experience a little shot of glee as this conversation unfolds, mainly because we can examine the question. If I may turn it around for a moment: Verdi was the perfect candidate to write astutely for the Catholic Requiem Mass, precisely because he was an agnostic in the institutional sense of the term. By the time he had made his first attempt at the Libera me, Verdi had lived a full life during an era where religiosity not dogma was the measure of expectation. In other words, both collective and individual religious feeling was understood to be part of a social dimension. These sentiments were frequently channeled into nationalistic projects as we’ve seen. Individuals like Verdi often framed their own religious views as integral to the drama of the human condition. Put another way, if you could demonstrate your expressive conviction, it didn’t matter how you got there. Despite the attempts of his enthusiastic fans to ensure his god-like status Verdi wasn’t above the fear of his own mortality and he had a stupendous dramatic gift. By all accounts in late nineteenth-century Italy, the Requiem text and its message was like physical gravity. You simply didn’t consider the world without it. You didn’t have to believe in it. It happened to you.

Although it hadn’t always been an overt part of his public persona, Verdi’s study of older music was more than just a passing interest. On one occasion, he made some cliff notes about some key figures in music history. His entry for J.S. Bach reads “Sebastian Bach, born in 1685, genius, the style, original and abundant.” Verdi also had a large personal library at his home in northern Italy, Sant’Agata, that included works by Palestrina and other older composers. He also pursued his historical interests by exploring the rich treasures of the Italian archives. His trip to Naples to study some older manuscripts became the subject of some infamous caricatures.

At the end of his life, Verdi’s austere views on conservatory education were old-fashioned by modern standards – his advice included things like “don’t forget your daily doses of fugue.” But Verdi’s outspoken discontent with the Italian fascination for the new also gave him renewed authority. After all, it was a potent idea for a master of Italian opera to embrace older composers – associating yourself with Palestrina meant you were in pretty good company! In a sense, Verdi was admitted into a type of secular sainthood from his embrace of older music.

In truth, the Requiem draws from both the tradition of actual church music and the representation of church music in the theater. I draw that division for us, not for Verdi, because it didn’t seem to matter very much to him in the course of composing. The Requiem quotes some of his opera music, for example the 2nd movement shares a melodic idea with quasi-religious scenes like this one, at the beginning of the Third Act of Aida. That same musical idea, with its religious associations, turns up in a completely different context in Falstaff, this time in the Third Act as a mock litany.

Verdi may have been knowledgeable about church music conventions, yet his re-creation of late Renaissance music is harder to pin down. There is the psalm verse at beginning of the Requiem, where the choir sings alone in a restrained imitative style. Or there is the music that references plainchant, or harmonized recitation tones. You can hear these techniques in the Libera me. Verdi delivers the ancient words with his own composite language, drawn from his knowledge of older techniques and his lifetime of music for the stage.

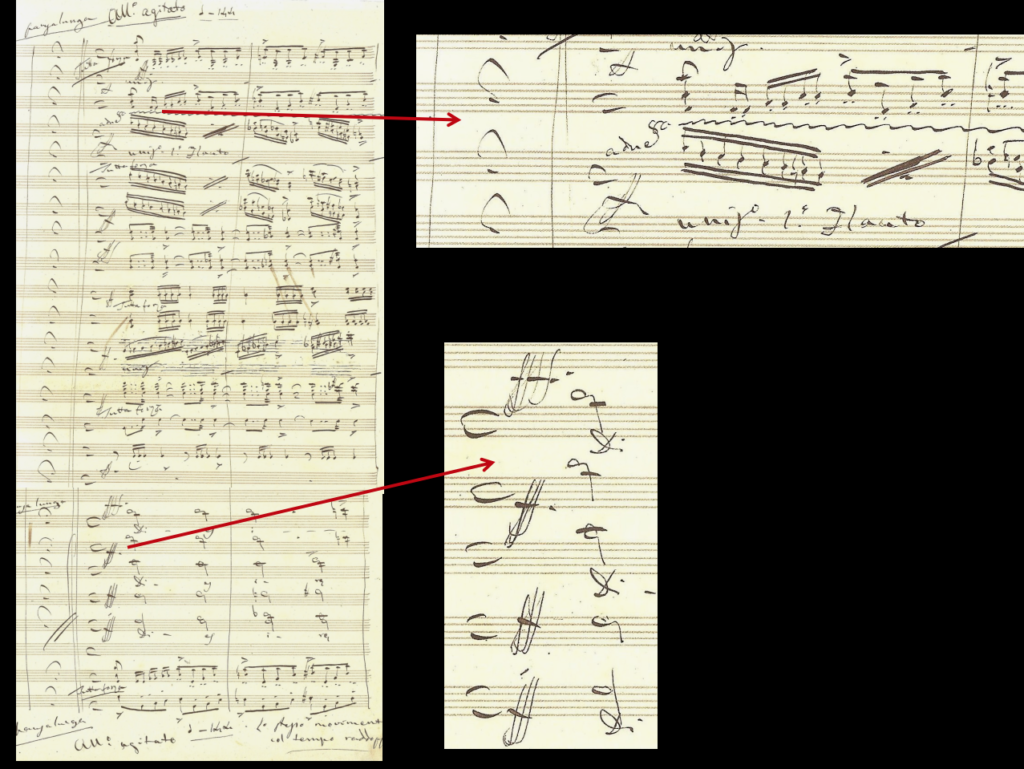

If we want to find the clearest connection between the early Libera me and the Requiem, we must look to the medieval sequence Dies irae. This was the first music that he wrote for the Requiem text. Verdi envisions a terrifying apocalypse, with dramatic blasts in the bass-drum and searing passages in the strings and woodwinds. This is the kind of music that asserts itself without argumentation or moderating force. It is calamitous and even strangely addicting; our only recourse is to hang onto our seats and hope for the best.

In its over-arching form, the Dies irae text was an opportunity for Verdi to enact the path of the individual. In the middle sections, he casts the soloists as characters in that drama. They take each verse in turn, the score begins in the low registers with the bass solo and reaches to the climactic moment in the Rex tremendae until things change course and fall toward the Lacrymosa. In this sense, the moment acts like a fulcrum for the entire movement. If the Requiem was a mirror for nineteenth-century stories about belonging, the second movement is a much older story about terrified sinners, in their infinite variety.

PERFORMANCE: REQUIEM AND KYRIE

From its earliest conception, the Requiem has been a powerful mirror for anxieties about belonging. The mirror was private and public – private, in that Verdi saw its potential to glorify the things he held most dear – and public, in that the work generated debate about the essence of Italian music.

After all, nations imagine themselves into being too. They are also the product of perception. In the nineteenth-century many larger communities in Europe were engaged in this kind of imagining. They were doing what communities often do when trying to build a collective identity. They fashioned their stories by explaining – often in humorous or ruthless terms – how they were superior to their neighbors. For the Italians, it was the Germans to the north that caused the most anxiety. When Verdi conducted his Requiem for the first time in Milan in 1874, Italian ambivalence over the Franco-Prussian War was still fresh and the Italians themselves had just ended a long process of unification. Verdi claimed that his Requiem memorialized the famous Italian poet Alessandro Manzoni – in sum, a tribute by one great embodiment of Italian culture to another. But like so many other works by major composers offered in the public arena, the Requiem became a convenient target for thinly-veiled politics.

In one of the more famous examples of this kind of cultural anxiety, the noted German conductor, Hans von Bülow wrote that Verdi’s new work was nothing more than an Oper in Kirchengewande (opera in ecclesiastical dress). Whether or not Verdi actually committed a transgression by allowing the drama of the stage to inform the language of the liturgy wasn’t really the point; better to think of it as yet another way that Verdi’s work became a kind of cultural dartboard. In addition to providing juicy entertainment for the Italian press, Bülow was re-enacting an old aesthetic argument from home, which usually painted a picture of Beethoven as the embodiment of truth and Verdi’s predecessor, Rossini, as the incarnation of a shallow beauty.

The Requiem was also a private mirror, one perhaps less easy to identify, but more potent for our twenty-first century perspective. In fact, Verdi himself was ambivalent about the whole business of religion. He was a self-proclaimed agnostic. For the people on this stage, this fact has been a source of animated conversation over the last weeks. It goes something like this: “Clearly it would be preposterous to suggest one has to be a devout Catholic to write good Catholic music.” And then … “But it can’t be true that this music is sacred just because I’m convinced it is. Am I dreaming? Look at my part. This music does have the exquisite force of conviction.”

Now for my own confession: I experience a little shot of glee as this conversation unfolds, mainly because we can examine the question. If I may turn it around for a moment: Verdi was the perfect candidate to write astutely for the Catholic Requiem Mass, precisely because he was an agnostic in the institutional sense of the term. By the time he had made his first attempt at the Libera me, Verdi had lived a full life during an era where religiosity not dogma was the measure of expectation. In other words, both collective and individual religious feeling was understood to be part of a social dimension. These sentiments were frequently channeled into nationalistic projects as we’ve seen. Individuals like Verdi often framed their own religious views as integral to the drama of the human condition. Put another way, if you could demonstrate your expressive conviction, it didn’t matter how you got there. Despite the attempts of his enthusiastic fans to ensure his god-like status Verdi wasn’t above the fear of his own mortality and he had a stupendous dramatic gift. By all accounts in late nineteenth-century Italy, the Requiem text and its message was like physical gravity. You simply didn’t consider the world without it. You didn’t have to believe in it. It happened to you.

Although it hadn’t always been an overt part of his public persona, Verdi’s study of older music was more than just a passing interest. On one occasion, he made some cliff notes about some key figures in music history. His entry for J.S. Bach reads “Sebastian Bach, born in 1685, genius, the style, original and abundant.” Verdi also had a large personal library at his home in northern Italy, Sant’Agata, that included works by Palestrina and other older composers. He also pursued his historical interests by exploring the rich treasures of the Italian archives. His trip to Naples to study some older manuscripts became the subject of some infamous caricatures.

At the end of his life, Verdi’s austere views on conservatory education were old-fashioned by modern standards – his advice included things like “don’t forget your daily doses of fugue.” But Verdi’s outspoken discontent with the Italian fascination for the new also gave him renewed authority. After all, it was a potent idea for a master of Italian opera to embrace older composers – associating yourself with Palestrina meant you were in pretty good company! In a sense, Verdi was admitted into a type of secular sainthood from his embrace of older music.

In truth, the Requiem draws from both the tradition of actual church music and the representation of church music in the theater. I draw that division for us, not for Verdi, because it didn’t seem to matter very much to him in the course of composing. The Requiem quotes some of his opera music, for example the 2nd movement shares a melodic idea with quasi-religious scenes like this one, at the beginning of the Third Act of Aida. That same musical idea, with its religious associations, turns up in a completely different context in Falstaff, this time in the Third Act as a mock litany.

Verdi may have been knowledgeable about church music conventions, yet his re-creation of late Renaissance music is harder to pin down. There is the psalm verse at beginning of the Requiem, where the choir sings alone in a restrained imitative style. Or there is the music that references plainchant, or harmonized recitation tones. You can hear these techniques in the Libera me. Verdi delivers the ancient words with his own composite language, drawn from his knowledge of older techniques and his lifetime of music for the stage.

If we want to find the clearest connection between the early Libera me and the Requiem, we must look to the medieval sequence Dies irae. This was the first music that he wrote for the Requiem text. Verdi envisions a terrifying apocalypse, with dramatic blasts in the bass-drum and searing passages in the strings and woodwinds. This is the kind of music that asserts itself without argumentation or moderating force. It is calamitous and even strangely addicting; our only recourse is to hang onto our seats and hope for the best.

In its over-arching form, the Dies irae text was an opportunity for Verdi to enact the path of the individual. In the middle sections, he casts the soloists as characters in that drama. They take each verse in turn, the score begins in the low registers with the bass solo and reaches to the climactic moment in the Rex tremendae until things change course and fall toward the Lacrymosa. In this sense, the moment acts like a fulcrum for the entire movement. If the Requiem was a mirror for nineteenth-century stories about belonging, the second movement is a much older story about terrified sinners, in their infinite variety.

PERFORMANCE: DIES IRAE

Since the 1930’s, the Requiem has been a staple of the choral repertory on both sides of the Atlantic. Common wisdom would have us believe that the work requires the world from its performers, but also gives it back in return. When Verdi sat down to write it, he had specific soloists in mind and the score is reflective of their special gifts as technicians as well as interpreters. Because we can compare the earlier source, we know that Verdi re-wrote the music with the talents of a particular singer in mind.

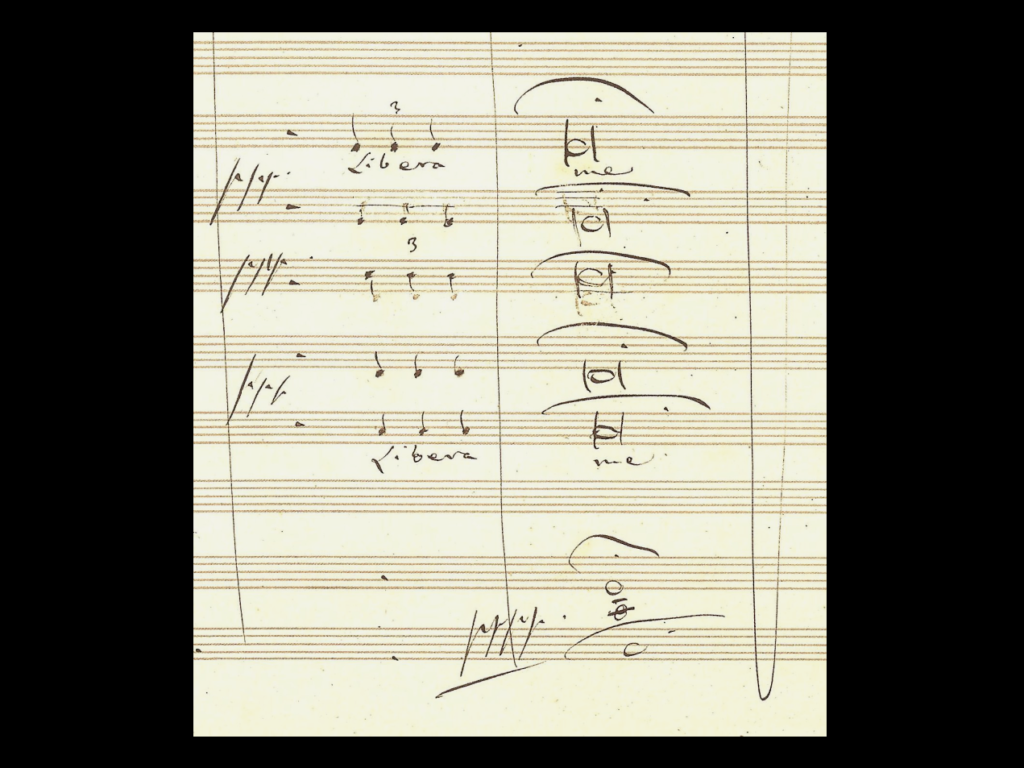

Her name was Teresa Stolz. She was born in Bohemia but she spent most of her career in Italy. Stolz was a powerful singer, both passionate and with exceptional technical control, and Verdi was enamored with her in more ways than one. She sang in several of his operas, including Don Carlo and Aida. Verdi wrote for her without concern for technical limitation. He enhanced the soprano part in a variety of ways. He added measures. He made her part higher and more virtuosic. He also gave her music that was originally given to the choir. These changes tend to happen in prominent places, like the end. In the older version, the choral basses have the part, but in the final version it is the soprano that murmurs the last few moments.

It must have been impossible for Verdi not to have remembered Stolz’s extraordinary voice as he composed. This meant he also prepared for her presence in the score by saving the force of her dramatic impact for later. In one instance, he examined an older passage featuring soprano and choir alone. He took the melody from the soloist, gave it to the orchestra, shortened it, and then placed this passage at the beginning of his new work. In the Libera me, you will hear something that sounds like the very opening of the Requiem but this time it is led by the soprano in its full poignancy.

The Requiem text also allowed Verdi to explore the voice in ways that he couldn’t in his operas. This may sound kind of surprising because we’re used to thinking of his operatic writing as a complete exploration of the voice. But here I don’t mean expressive range — I mean “voice” in the poetic sense– in the sense of who is speaking. In opera, characters are delineated. Their relationships with others and with themselves are the tensions that push the drama forward. In this work, these roles aren’t so clear cut. In fact, they are often exchanged. The singers must ask themselves “am I telling a story about someone else?” or “Is this my voice, must I embody these words?” In this way, Verdi complicates the medieval poem and its spiritual meanings.

Sometimes the move from characters to story-telling is blatant, like the return of the Dies irae music. You don’t need me to tell you when this gripping music returns. You can’t miss it. But why this music at those particular points? Why would Verdi go out of his way to break the flow of the story? The answer, at least in part, is that the Dies irae music forcibly tears the soloists away from one role to another. At one point the soloists move from their role as narrators to fearful sinners who plead for their own salvation. “What can a wretch like me say?” But these are the obvious shifts in poetic voice. Verdi sometimes clouds the issue for everyone involved. This happens in the Rex tremendae, where the bass temporarily stops being a character and aligns himself with the narrative voice of the choir.

I return now full circle, back to the genesis of the Libera me. We can appreciate again the opening for its drama, but perhaps now we can also see its shifts in character. The soprano begins freely in a kind of monotone chanting. Suddenly, she releases herself and embodies her fearful predicament; her line becomes more articulated, more angular, more urgent. In a few short bars, Verdi has read musically against the grain of the text. He does this throughout the work – asking the singers to morph between worlds and sometimes to live between them.

This blurring of story-telling and embodiment makes this work richer and its paradoxes more immediate. We are about to experience an upbeat fugue for double chorus, and a gentle set of theme and variations in the Agnus Dei, but soon enough we come upon those questions again. The last movement ends with the soprano grounded in the dark regions of her voice, in steady prayer. We could say that all is resolved but the epic questioning that preceded this, makes it an uneasy promise.

My own approach to the Libera me tonight will be that of a reflective witness. Verdi’s work is a testament to his private questions but it survives in ways that he never could have imagined. How will you imagine this work? How will you reside in its infinite stories?

PERFORMANCE: SANCTUS & AGNUS DEI

Libera me/ Deliver me

What is the final consummation of all things?

Does it rely on the self?

Is it the sum of our journey together?

Who is our guide in death, in judgment, in heaven, in hell?

What of the body?

What of the soul?

What is this great divide between them?

Libera me, Domine/ Deliver me, Oh Lord

What is the shape of grief?

What of remorse?

Dum veneris judicare/When you will judge

How will we recognize the earthly signs?

Dies irae/Day of wrath

What of the great fire?

How do we sing in the face of such terrible and mysterious truth?

How do we weigh guilt?

What of the rational?

What of moral evil and the will?

What if immortality is a grace and not of the soul? What then?

What of my falling away from faith?

Requiem aeternam/Eternal rest

What is the face of peace? Of the blessed?

free floating

What of the self?

Is judgment specific? Is it universal?

What is the price of admission?

What of my denial?

***

What of that great ushering to the end?

What will guide our exodus together?

***

Is our fate temporary, or eternal?

What is the form of our survival?

What will be our retribution?

Will there be justice?

Et lux perpetua luceat/ And perpetual light

What of renewal?

How is our future shaped by our present?

What of the demands of fellowship?

Why this craving for the good?

Libera me, Domine/ Deliver me, O Lord

If we say the same thing over and over, is it true?

Who are the players in this struggle?

Can there be salvation through violence?

When has force, failed?

Libera me/ Deliver me

What of surprise?

When to speak? When to sing?

When to ask questions? When to accept?

***

Is there forgiveness?

Can light lead to doubt?

What is the final consummation of all things?

How will the new heaven and earth take our place?

Does it rely on the self?

Is it the sum of our journey together?

***

Can only the appeal to mercy remain?

Who is our witness?

How do we live on the shadowy side of hope?

PERFORMANCE: LIBERA ME

– Laura Dolp

EVENT

Verdi ‘Behind-the-Scenes’

Montclair State University Chorale

Heather J. Buchanan, conducting

Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ; November 2009