Gambling the World: Carmina Burana in America

ABOUT THIS FILM

In 2017, I made a short film in collaboration with my colleague Dave Sanders and students at the School of Communications and Media at Montclair State University. Its purpose was to introduce Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana before a multi-disciplinary performance of the work by the University Chorale and dancers from the Department of Theater and Dance, conducted by Heather J. Buchanan. I co-produced the film with Dave Sanders. I also wrote the script and did the voice over. Sound design was provided by Christopher Sabo, Peter Fumosa, and Michael Ott.

When I was invited to think about Carmina Burana, I knew immediately that I wanted to ask hard questions about it. The result is a film that isn’t comprehensive, nor is it safe. It does provide some introduction to Orff’s work, but my primary goal was to use Carmina as a foil to think about larger and more tangled issues about music and its practitioners. I was interested in the following questions: What is the relationship between the living work and its historical maker? Whose version of the past do we embrace, and why? Why do certain works become iconic? In our own confrontation with iconic works, how do we question them in a meaningful way? Finally, what kinds of responsibilities do we have as interpreters and listeners?

FILM SCRIPT

In 1939 on the eve of the Second World War, the British poet W.H. Auden wrote from New York: “As the clever hopes expire / of a low dishonest decade: / Waves of anger and fear / Circulate over the bright / And darkened lands of the earth.” Auden’s fearful sentiments haunted not only his own generation, they have a peculiar resonance in the current landscape of American politics.

What follows involves both the past and the present. It is a story of creative energy, of nostalgia, of ambition, of fear, of resistance, and human fallibility in the game of life. Its centerpiece is one of Auden’s contemporaries, the German composer Carl Orff; whose music is renowned for its gripping drama and a visceral quality that is often inversely proportional to its demands on our rational intellect.

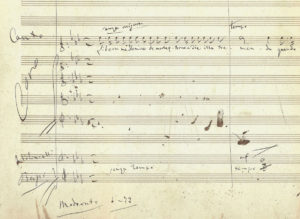

Three years after Auden’s prophetic poem, Orff wrote the cantata Carmina Burana at his home in Munich. The work enjoyed considerable success under the Nazi regime and Orff’s career was secured by their financial support. Orff called his dramatic concept “Theater of the World” where music, movement, and speech were inseparable, and the musical score, in every moment, was connected to the action on stage. A few modern productions have re-visited Orff’s original idea, such as the performance you will experience today.

Carmina Burana otherwise known as “Songs of Beuern,” is named after the Bavarian monastery, Benediktbeuern, where the medieval texts were first discovered. Orff first encountered the poems in a nineteenth-century collection. His cantata sets 24 of the multi-lingual poems, including ones in Medieval Latin, Middle High German and Old Provençal. Collectively, they address the ephemeral qualities of life, the unreliability of material wealth, and the dangers of gambling, lust, and gluttony. Orff organizes these songs into thematic tableaus such as the pastoral green, the tavern and the court of love.

The piece begins with the seductive and terrifying cycle of the turning Wheel of Fortune, a concept that pervades its medieval poetic model, and one that the dancers today use as part of their inspiration. An extraordinary illumination of this Wheel appears in the Codex, with four Latin phrases on its periphery: “I shall reign, I reign, I have reigned, I am without a realm.” Orff turns this wheel metaphorically between scenes and sometimes even within a single movement, turning joy into bitterness, and hope into grief. Fortuna also returns at the end.

That said, medieval allusions do not extend to Orff’s musical language. He composes in a straightforward modern style that builds its interest through repetition and assertion, steering clear of organic development or complex textures. At times, Orff uses Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Les Noces as a musical model. In the court of love, for example, the choral mantras mirror those in Stravinsky’s ballet. More generally, Carmina draws on Stravinksy’s orchestration and his habit of lascivious neo-pagan storytelling.

Like Orff’s dance with the circumstances of his own life, his twelfth-century source is ripe with allusions to games of brilliant strategy. The medieval wheel and the truth in wartime Germany – like the truth in present-day America – morphed with their conditions. Since the Second World War, Orff’s music has served a dizzying array of contemporary uses, including film scores and advertising. It is, in the words of one commentator, an “instant tape loop for the mind” that reverberates in its listeners.

Orff’s music is no more inherently rightist propaganda, than it is leftist propaganda. But it is hard to forget that it has been eagerly appropriated for some of the most primitive, toxic and unreflective periods of human history. Perhaps we should ask: can we own the world of Carmina Burana, rather than it owning us? Can we change the rules of the most serious game of all? … transforming its players and listeners into a community of clear-sighted dissidents …where bombast is assigned its rightful place, where content is returned to human speech, and where we ride the Wheel of Fortune consciously?

– Laura Dolp

EVENT

Montclair State University Chorale

Heather J. Buchanan, conductor

Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ; May 2017